In sleepy Naxalbari, people are breathing new life to emerge from the shadows of a failed Maoist revolution that continues to be the village’s only calling card. With their barely disguised tone of frustration, they now make it clear that for decades, the story of Naxalbari, which nestles at the base of cloud-kissed hills, had been one of continued violence, businesses closing, classrooms shrinking and communities withering.

But not any more.

Naxalbari’s 250,000-plus population is now taking advantage of India’s burgeoning $15 billion e-commerce market, picking up jobs in sectors ranging from insurance, finance, trading, infrastructure to tourism, education and agriculture. The residents — largely tribal members of a quiet, farming community, the rest of them micro-entrepreneurs, employees of white goods traders and timber merchants — say that they have tasted economic growth. They now wish to talk business and do not find the change unsettling. They, in fact, do not even care that their homeland is still considered the incubator of India’s epic class war that kills a little over a thousand people every year.

The leading light of this armed struggle was ultra-left leader Charu Majumdar and his close associates Kanu Sanyal and Jangal Santhal, who planned and mobilised tribals for months before the outbreak of Naxalbari uprising on May 25, 1967. Majumdar and his associates belonged to the radical stream of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), which was inspired more by Mao Tse Tung’s idea of peasant rebellion than Marx-Lenin’s vision of class war. The Chinese Communist Party Revolution under Chairman Mao, which achieved a sensational victory over the nationalist government under Chiang Kai-Shek through an armed peasant rebellion in 1949, had left a deep impact on Majumdar and Sanyal. Inspired by Mao’s success, Majumdar published his famous Eight Documents in 1965, arguing that the CPI-M should endorse Mao’s strategy of armed rebellion against the Indian state.

But everything went up in smoke after Majumdar died in police custody in 1972, and the West Bengal government brutally crushed the radicals.

Naxalbari, five decades on

Five decades later, economic growth, not revolution, is driving Naxalbari, the one-road village that was in the news recently when BJP president Amit Shah launched the expansion of his party in West Bengal. Before Shah had arrived, Naxalbari — actually — had fallen off the headlines.

Livelihoods are still tied to the earth in Naxalbari where a little over 59 percent are connected with agriculture. In balmy June, women dry grain on cemented roads to remove the chaff while others pick the summer flush of leaves from sprawling tea gardens to be processed for sale across India, and the world. Some feed cows inside muddy pens that line the roads, and the pace is still slower than what one usually experiences in a bigger city. Nearby, a small red flag flutters in the monsoon winds, overlooking busts of Maoist leaders perched on red pillars, for long considered the ubiquitous symbol of violent revolution.

Growth is the new change in Naxalbari, now synonymous with its emerging skyline of grain elevators, Hero motorbike showrooms, departmental stores, designer weddings and well-stocked bars chock-a-blocked every night with teenagers high on Bengali pop music, whiskey, and super-strong beer branded as Godfather.

Six gram panchayats make up the Naxalbari block, all a patchwork of old tea estates. But there’s a new rush in the air, thanks to the expansion of the National Highway that cuts through the area into a six-lane road. New flyovers are being constructed, real estate is at a premium.

“For almost one and a half decades starting in the late Sixties, people living here suffered immensely, not any more. Naxalbari is not even iconic now because the romance of revolution is all but over. People of Naxalbari are like people from any other city in India,” claims Taposh Bose, a senior manager of a finance and leasing company. Bose, an amateur singer, sat at a roadside tea stall in Naxalbari and discussed songs of Justin Bieber with a handful of college students who had traveled to Mumbai to watch the Canadian performer.

Even three decades ago, they would be talking about peasant movements. The students were happy to record portions of the Bieber performance on their smartphones that they had acquired through e-commerce sites like Flipkart. At least three students ordered smartphones a week before their journey to Mumbai, happy that the delivery (complete with selfie sticks and anti-radiation stickers) was right at their village doorstep.

Bose says it is a six-letter word that has changed lives in Naxalbari, and other small towns and growing villages across India. It is “Access”. Bose, who lives in adjacent Siliguri town, the gateway to India’s northeastern states, should know.

“I have my world on my laptop, my Flipkart orders reach the next day. In a city like Siliguri, where speakers are not easily available, I got mine through Flipkart,” says Bose.

His focus, once again, is on access and availability.

A digital revolution is steeping

At Hatighasa village in Naxalbari zone, where a police inspector was killed by an arrow that came from a crowd of protesting tea garden workers on May 24, 1967, villagers say there’s no need to fight powerful landlords any more because there are none. Last week, angry tea garden workers blocked a highway for a few hours and got a planter arrested because he had turned violent. “We used WhatsApp to send the planter’s details to the cops, we shared the recording of his turning violent. He was arrested within minutes,” says Budhon Oraon, a tea garden worker.

The entire crisis was over in a couple of hours and the workers returned to the gardens. “We didn’t even talk about the incident; we watched India play Pakistan in the Champions Trophy finals, and we mourned the loss,” laughs Oraon.

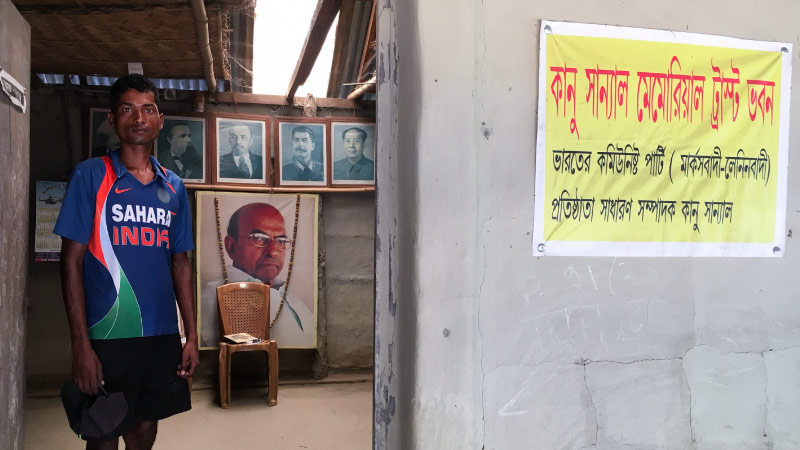

He, however, admits there are times when the villagers are egged on by a handful of suave Marxist ideologues from Kolkata to rally against oppression. On the 50th anniversary of the Naxalbari movement early this year, a few hundred workers and political activists gathered at the dilapidated residence of the late Naxalite leader, Kanu Sanyal, to talk about the peasants’ movement.

“It was just a day-long affair, then Sanyal’s hut was locked up, and all left. That was the end of the anniversary meeting,” says Cyril Murmu, a mason.

Murmu says the extremist, violent ideology that was once in vogue does not find any political space in Naxalbari; he calls it just another slice of 21st-century India. He is sanguine that the caste-based feudal superstructure that the Naxalbari movement set out to annihilate still exists in some quarters in India but remains diluted. “It is a market economy, there may be inequalities but no scope for violent deaths, armed struggle.”

Time and again, he helps his family members to acquire “something or the other” through Flipkart. His son mostly seeks electronic gadgets and tees, his daughter sunglasses and perfumes. There have been occasions when visitors who come to Naxalbari for a glimpse of Kanu Sanyal’s home and busts of the Indian and Chinese Maoist leaders have used his son’s selfie stick to take photographs.

Murmu stands bare bodied outside Sanyal’s home — a single room hut thatched with corrugated tin, it lies in a dilapidated condition. A portion of the roof has cracked, sun-rays light up the room where his books, notepads and clothes lay in a heap along with steel utensils.

“He was a recluse, totally disillusioned after the failure of the movement, and eventually hanged himself,” says Dukhiram, a young boy who helped open the doors of the house. Dukhiram, who wore a tee of the Indian cricket team, said he is a fan of the Men in Blue and keeps track of every match the team plays, in India and abroad. His sister, a nurse at a Delhi hospital, sent him the Indian cricket team’s tee, which she purchased online.

In the Dooars, connectivity opens new doors

People at a nearby restaurant operated by Nepali-Indian Gurkhas say their demand for Gorkhaland is important for them because they gained nothing from the failed Maoist movement.

Ranjit Thapa, 29, who often stands at the highway linking Naxalbari with Siliguri bearing a Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM) banner, says he works hard at his restaurant, earns a decent income, and constantly buys gadgets, shoes, dress materials and books through e-commerce sites like Flipkart and Jabong. “The internet has opened the world to me, these e-commerce sites bring the world to my doorstep.”

Thapa’s wife and two daughters swear by Flipkart. E-commerce, he claims, has helped people get what they desire at the “right rates”. In small blocks like Naxalbari, people are extremely price-conscious.

Standing next to him, his friend Animesh Poddar, 45, says he is using the very e-commerce sites to sell tea, even perishable products like jackfruit. “The armed struggle brought the nation’s spotlight on Naxalbari, now the spotlight is on the town’s new breed of entrepreneurs, students and traders,” he says.

It is clear that Naxalbari’s middle-class is enamored with India’s rising global status. They have instant answers for everything through their handsets — more powerful than any nuclear weapon — which helps them access the world.

“Naxalbari is now far removed from the violence that is carried out in some parts of India in its name. It has — almost two and a half decades ago, a decade and a half ago — shed its radical past,” says Siddharth Subba, a resident of next door Bagdogra, a cantonment town that is home to the region’s only airport.

Subba, an avid customer of Flipkart, says the government’s redistribution of land has helped many acquire their own farms, through they remain dependent on the weather gods. “The peasants and tea-workers of the region are better off now than nearly a half-century ago when they were pushed to the brink and took up arms,” says Subba. “The young generation is hooked on smartphones and video chats. They order everything through Flipkart — from specially designed mugs to impress girlfriends, to mozzarella cheese. Where is Lal Salaam in this?”

“We are ordering almost every month, and we always get the product on time, good rates. There are times when I ask my family members not to go overboard,” laughs Subba. He feels the growth of e-commerce in Naxalbari has helped people raise their aspiration levels.

“The majority of tea garden workers have a cellphone they have acquired through an e-commerce site. There is an advantage: deliveries will happen even if there are strikes in the towns and shops are closed. In some ways, there’s a guarantee that comes with the order,” adds Subba.

Recently, one of the restaurants at Naxalbari decided to acknowledge the community’s diversity. The owner added some less traditional items to the menu of fish, mutton, chicken and rice: Chicken-fried steak and burgers. Residents in Naxalbari flocked to the restaurant, some even packed steak for home, admitting such fare was all but extinct in a place where longtime residents would quietly work in tea gardens or rice mills and eat frugal meals. The only holiday season was the annual Durga Puja celebrations.

“Now we have Valentine’s Day parties,” says Swapan Nath, a worker at Naxalbari’s only watering hole. A week before Valentine’s Day, orders for gifts go on a high on e-commerce sites. “Things are changing fast, everyone knows how to grow, what to seek,” says Nath.

Nath says new residents of the village are investing in real estate, even buying portions of tea gardens, reopening shuttered storefronts with groceries, and, in the process, extending the lives of local communities that seemed to be staggering towards nowhere. This, claim locals, is an interesting demographic shift that has been uniformly welcomed in Naxalbari where once tradition was seen as the central charm of rural life.

A fresh breath of life in Naxalbari

“Naxalbari is about life, not death anymore,” claims Indraja Dutta, who lives in Siliguri and has heard countless stories about the tumultuous days from her parents. “They started changing from the mid-1980s and now have different set of priorities,” says Dutta.

She is an avid Flipkart customer, with orders ranging from perfumes to dresses to gadgets. “It’s a wonderful way to remain connected with the world,” she says. “Every week I get offers. I know I am not missing out on anything despite being in a small town.”

And no one is worried about this unexpected multicultural mix in Naxalbari. They think this must be the vision of what the future of a city so iconically linked with armed revolution look like. “The face of villages are changing, becoming small towns. Naxalbari can no longer live on its violent past, it needs to make the current strong enough to merit attention,” says Suman Bhattacharya, a veteran journalist who was once actively involved in the Naxalite movement.

Bhattacharya says leaders of the Naxalite movement did not leave behind any legacy for the locals to follow. He says in next-door Nepal, Maoist leader Prachanda, a two-time prime minister, is known as Pushpa Kamal Dahal ever since Nepal adopted a multi-party democracy in 1990. “The Left leaders in India are blaming the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party for destroying the legacy of Nehru and Gandhi; probably they deliberately do not wish to remember that they spent a lifetime criticizing these two national icons,” adds Bhattacharya.

Residents of Naxalbari, it looks clear, do not wish to retain and continue the legacy of the Maoist foot-soldiers.

“Without change, Naxalbari would be a ghost town,” says Asheem Burman, an employee of the Indian Railways who works at the Naxalbari station that handles a little over 14 trains a day, including a long-distance from southern India twice a week. Goods worth ₹3,000 crore travel to the northeastern states through a single-line railway running through a small corridor known as the “chicken’s neck” near Siliguri.

Burman, who flags the trains, says the railway station — during the violence-prone days of the late 1960s and early 1970s — was surrounded by jungles. Only the rich had electricity, and the “power”.

Today, every house has electricity, nearly 75 percent of the villagers are literate, and more than 60 percent of the 220,000-strong population is less than 35 years of age, of which an estimated 30,000 workers from Naxalbari add value to North Bengal’s burgeoning economy.

These are fresh steps in what was once considered the first, giant step in the great Indian proletariat revolution.

“We will continue to progress,” says Murmu. “We don’t want to regress or stay the same. Life is pretty dull when that happens.”

That’s Naxalbari in 2017.

Shantanu Guha Ray is a journalist based in New Delhi.

Photographs by the author

Lead image design: Arjun Paul

Customer data analysis: Nipun Sharma, Prasanthi R, Nitin B and Vijay Jayanti. Outreach by Arjun Paul